Arte Araba Al Cairo. L’Art Arabe d’apres Les Monuments du Kaire depuis le VIIè Siècle Jusqu’a la fin du XVIIIè. THREE VOLUMES.

Prisse d’Avennes, Achille Constant T. Emile.

Synopsis

Prisse d’Avennes was, in many ways, a paradox. An artist of consummate skill, he was also a writer, scientist, scholar, engineer and linguist, a genius who spent much of his life among the illiterate. French to the bone, he was of British blood; a European, he embraced Islam and took the name Edris-Effendi. By nature contentious, he alienated colleagues, yet succoured the sick and the poor. Of the hundreds of 19th century Western artists, scholars and writers who gravitated to the Islamic world following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, few possessed so prodigious an intellect, such a trove of talents, so insatiable a curiosity or so passionate a commitment to record the historical and artistic patrimony of ancient Egypt and medieval Islam. He succeeded brilliantly, yet he failed to achieve the stature to which his successes entitled him, both during his lifetime and in the 111 years since his death. He remains, as arts writer Briony Llewellyn calls him, “a shadowy figure in the history both of Egyptology and of European response to Islamic art.”

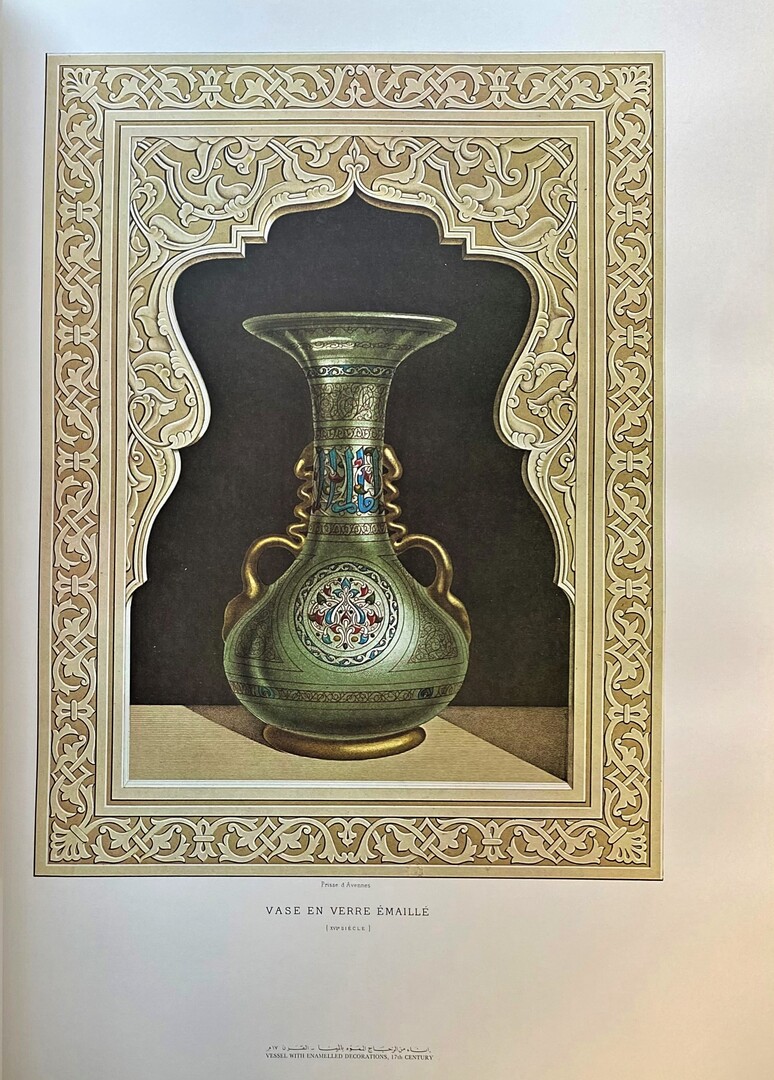

Prisse d’Avennes was a fine artist and an outstandingly brilliant observer who recorded much that has since disappeared. In this monumental work he recorded Arab Art in Cairo through splendid plates of architectural studies, mosaics, ornaments, interior designs, textiles, carpets, civil and religious furniture, Islamic book binding, miniatures, and different types of Qur’anic script. [Reference: For the first edition see Creswell, 81].

Prisse wrote for scientific journals, published treatises and kept active in learned societies, while working on L’Histoire de L’Art Egyptien” and L’Art Arabe. He made excursions to Egypt, worked on the Egyptian exhibit for the World Exposition of 1867 and was director and chief hydrographics engineer for the French company charged by Isma’il Pasha to produce a plan for the exploitation of the lakes of northern Egypt. When the pasha cancelled the project at the last moment, Prisse resigned the post and, for the next 10 years, devoted himself exclusively to his masterworks, the astounding energies of his youth clearly intact. Apart from the literary demands, Prisse trained teams of artists especially to prepare the plates for his book, monitoring their work relentlessly, until each plate precisely replicated the original drawing. L’Histoire de I’Art Egyptien, published in its entirety in 1877 by the Librairie Scientifique of Paris, consisted of two volumes containing 160 plates and a separate volume of text written by P. Marchandon de la Faye on the basis of notes by Prisse, who was forced by circumstances to accept this arrangement. Illustrated sections on architecture, sculpture, paintings and industrial arts underscored the close correlation between the arts and the history of ancient Egypt, Prisse noted, revealed the course and progress of Egypt’s civilisation, its surprising customs and its religious thought.

Shown “with excellent splendour” at the World Exposition of 1878, L’Histoire de l’Art Egyptien became an important part of the body of Egyptology and, in that sense, Prisse’s hopes were fulfilled.

But for L’Art Arabe, he wanted more. He wanted to inspire the artists and architects of his time with fresh ideas to counter “the poverty of invention that so justly inflames those who profess to worship beauty.” Above all, he wanted to stir the public to understand and appreciate the epoch whose art had graced a millennium and inspired the Renaissance. “We affirm,” he wrote, “that not since the fall of the Roman Empire has there been a people more worthy of acquaintance, whether we direct our attention to the great men it has produced or contemplate the prodigious advances of the arts and sciences among the Arabs across several centuries.” The three atlas volumes of L’Art Arabe, published in parts by V A. Morel et Cie. from 1869 to 1877, contained 200 plates, 137 were chromolithographs, mainly by Prisse. Most of the remaining plates were tinted lithographs, several by Girault de Prangey, whose scenes of Cairo had earlier been published in his Monuments Arabes d’Egypte, de Syrie et d’Asie Mineure. A quarto volume of text by Prisse, embellished with dozens of illustrations offered essays on the caliphs, the Mamluks and the Ottomans to the time of Bonaparte; on religious, civil and military architecture; on arts related to and independent of architecture; on the origin, development and decay of Arab art; and, finally, on the plates themselves.