The Ruins of Gour Described and Represented in Eighteen Views, with a Topographical Map.

Creighton, Henry.

Synopsis

VERY RARE AND SCARCE COPY. Creighton was the Superintendent of an indigo factory at Gour, in eastern India. He was an excellent amateur painter and in order to find subjects for his paintings, he frequented the ruins of Gour at his leisure hour. Gradually, from his pastime he developed a serious interest on these ruins and antiquities. At the time of writing, Gour was ‘regarded as an immense quarry, whence bricks had been carried to Malda, Murshidabad, Rajmahal, and other places, and many majestic and beautiful edifices of great antiquity had been thus destroyed. Marbles and stones, being rarities in Bengal, were the objects of constant depredation, which was so ruthlessly carried forward that some noble structures were defaced or undermined for the sake of a few blocks or slabs of marble built into their brick walls’ (Lewis 1873: 130–1). Even Charles Grant, Creighton’s master, was a party to this despoliation. At his suggestion, St. John’s Church was paved with stones taken from these ruins, and sent down by him to Calcutta, at a cost to the church building fund of Rs 1,258. ‘Materials for floors, chimney pieces, and sepulchral monuments, were thus appropriated and carried off by anyone disposed to take possession of them’ (Lewis 1873: 130–1). In this scenario, Creighton worked in the opposite direction. He put in considerable labour to extricate richly carved architectural fragments and detached inscriptions from the deep jungles with which Gour abounded in order to prevent them from falling prey to the undertakers. He carefully recorded their place of occurrence and fondly preserved them in the courtyard of his factory at Guamalati.

These inscriptions and antiquities collected at Guamalati were later removed by William Francklin, Reginald Porch and other British officers to England and fortunately found their way to the major public collections of England and USA (Mitra 2010: 30–8). Creighton visited all the extant monuments of Gour, painted sketches of them, and even repaired some of the crumbling edifices like Firuz Minar (Mitra 2010: 13). He also collected the prized glazed bricks of Gour and coins, the latter ‘have been occasionally found among the ruins’ in his time. His antiquarian interests led him to Pandua where he prepared detailed architectural drawings of the Adina Mosque (Francklin 1910: 14) and probably other monuments, which never came to light. Gradually, he developed a large portfolio of drawings of the ruins of Gour and its vicinity. In 1801, he completed the first scientific survey of the city of Gour and prepared a detailed map of its ruins. He presented a copy of his survey map on a reduced scale to Marquis of Wellesley, the then Governor General of Bengal (1798–1805). A year after his death, in 1808, six of Creighton’s drawings were engraved and published by James Moffat in Calcutta. Still nine years later, in 1817, the result of his exertions at Gour was finally published in the form of a book entitled: “The Ruins of Gour: Described and Represented in Eighteen Views with a Topographical Map”, compiled from his manuscripts and drawings in the hope of providing some financial support for his family.

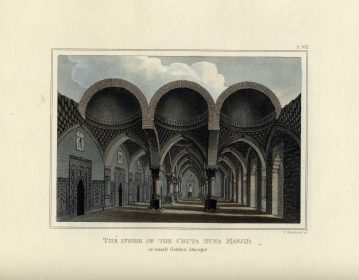

The aquatints are engraved by Thomas Medland, who was the drawing master at The East India Company’s College at Haileybury. The Map is etched by Thomas Fisher. The colour plates are as follows:

1. The Tower.

2. The Dakhil Gate.

3. The Chand Gate.

4. The Cutwaly Gate

5. The Suna Masjid, or Golden Mosque.

6. Chuta Suna Masjid or small Golden Mosque.

7. The Inside of the Chuta Suna Masjid or small Golden Mosque.

8. The Tomb of Shah Husayn.

9. The Painted Mosque.

10. A small gateway covered with a Dome.

11. Kadum Rasul, or the Prophet’s Foot, a Mosque.

12. Thanty Pa’ra.

13. Ruins of a Bridge.

14. Tombs at the small Golden Mosque.

15. Cham Kutta, a small Mosque.

16. Varaha Avatara

17. Siva’ni, a Hindu image

18. Brahma’ni and Bhawa’ni

Bibliographical References: Abbey Travel 438, Bobins II 794.